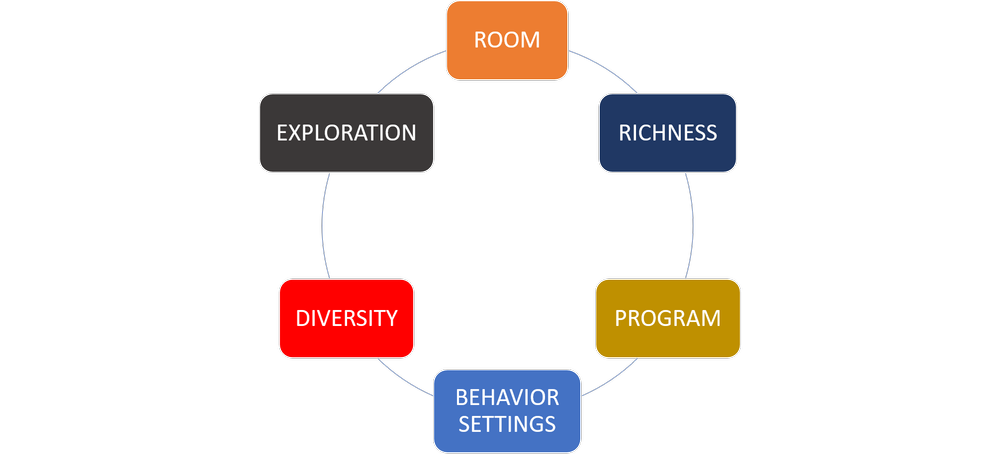

About this blog series: This is Part 5 in a series that explores the notion that people are creatures like any other, and there are basic characteristics that we seek, or need, in our habitats. Part 1, Intro is here.

BEHAVIOR SETTINGS

People are much more likely to stop and enjoy a public space if the space’s design clearly communicates what it should be used for. People need to be able to instantly recognize how they can use it – where they fit in. Ecological psychologists use the term “behavior setting” – the idea that people recognize specific settings in their environment for their utility, and this is a basic way we navigate the world.

For example, if we see a stove, cabinets, and a fridge, our brain registers that as a kitchen, and we instantly know what we can do in the space. If we see a dining table and chairs, likewise, we know what it’s for.

But many urban spaces are not thought through from this perspective, which means people can’t navigate them and just won’t use them. Still, other spaces don’t offer enough cues to make it convincing to us. A stranded bench by itself simply does not belong to a setting and as a result, we pass it by. I often wonder to myself, who would ever sit there? More often, though, I don’t even notice it – it becomes part of the background.

The term “behavior setting” was first coined in the 1940s by Roger Barker and Herbert Wright to express the complex combination of human behavior and physical environment. Their theory tried to explain how the physical and social environment can influence behavior, suggesting that people’s actions are shaped by the context in which they occur, such as the location, the people present, and the activities taking place. For example, behavior in a classroom setting will likely be different than behavior in a sports setting or a party setting. The theory posits that certain settings, or “behavioral niches”, are more conducive to certain types of behavior and that people tend to seek out and engage in activities that are consistent with their goals and values in those settings.

In their classic, but seldom-read book, One Boy’s Day (1951), Barker and Wright describe in detail a boy’s every activity from waking up to going to bed. To conduct their study, the team collected data on various public places in the town of Oskaloosa, Iowa, including events, meetings, and activities. They compiled lists of participants, schedules, and minutes of meetings, and recorded the goings-on at various locations, such as schools and churches. The study showed that in Oskaloosa, there were 585 public settings where people gathered at least once a year.

The study revealed that each place had a “standing pattern of behavior” that held true regardless of who was present or in charge. Thus, the idea of a behavior setting was born – the setting itself is instrumental in creating the behavior that takes place there. When it comes to behavior, the Who is less important than the Where.

Additionally, the social context of a public space can also influence behavior. For example, a public space that is heavily policed and has a reputation for being unsafe may discourage certain types of behavior, such as lingering or loitering, while a public space that is perceived as safe and welcoming may encourage those behaviors.

Convincing people to interact with a space is one of the principal arts of placemaking. Kathy Madden, one of my mentors at Project for Public Spaces, used to make the comparison that a well-run public space is like a great hotel. In a good hotel, there is always someone acting as the host, putting out fresh flowers, making people welcome, and making sure the lobby furniture is comfortable and beckoning. Likewise, a good public space manager is creating the setting, putting the seating into social arrangements, and moving them into the sun if it’s cold, or to the shade when it’s warm. They help orchestrate positive social behavior.

But even without an onsite manager, a public space needs to be clearly legible to any and all passers-by and convince them to enter and use it, with all the sensory cues that make using it not just a pleasure, but a must.